The Guardian, 2002

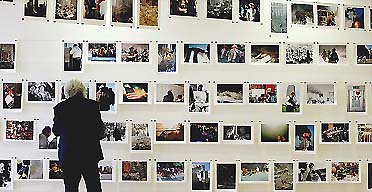

It became New York’s family album, a public scrapbook, a repository for pictures about September 11, in itself perhaps the most photographed event in American history. The pictures were hung in a small shop in downtown Manhattan, pictures taken on 9/11 and in the aftermath, at Ground Zero, from rooftops, bridges, in the wreckage, at the memorials. Taken by amateurs, professionals, fire-fighters, kids, cops, investment bankers. They called it Here is New York and it touched a nerve.

Over the year, people jammed into the little space in SoHo, almost a million of them. Tomorrow, on the first anniversary of September 11, there will be versions of Here is New York across America and around the world – in Tampa, Florida, and Louisville, Kentucky, in Chicago and Washington, Tokyo, Berlin, Zurich and London, where it opens at the Guardian Newsroom. A thousand photographs will be on display and another 2,000 can be seen on DVD. Entrance is free and profits from print sales will go to September 11 charities. The images can also be seen 24 hours a day on a monitor in the Newsroom lobby.

It started when Michael Shulan, a New York writer and part owner of the shop, put up a photo of the World Trade Centre in the window. He got a call from his friend, Gilles Peress, who was taking photos at Ground Zero for the New Yorker. Peress asked what he was doing. Shulan told him that he was watching some people looking at a photograph and was considering putting up more. “Do it,” Peress said.

They called Charles Traub, head of photography at New York’s School for Visual Arts, and the photo editor and curator, Alice Rose George. They decided the show should be open to everyone. Pictures would be scanned and then printed on inkjet printers, the prints sold for $25 each and the money given to kids who had suffered as a result of September 11.

They called Charles Traub, head of photography at New York’s School for Visual Arts, and the photo editor and curator, Alice Rose George. They decided the show should be open to everyone. Pictures would be scanned and then printed on inkjet printers, the prints sold for $25 each and the money given to kids who had suffered as a result of September 11.

“Here in New York is a very small part of the story of 9/11,” Shulan says. “In its own way it became a microcosm of what took place in the disaster’s aftermath at Ground Zero and elsewhere in the city. Not an art exhibition in the conventional sense, it was partly an impromptu memorial, partly a rescue effort and partly a testimonial of support for those actually doing the rescuing. It became a rallying point for the neighbourhood and the community at large.”

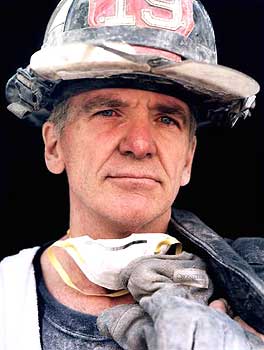

The photographs achieved what TV coverage never could: they provided a way for people to look and think, reflect and grieve. Firemen came in looking for images of their mates who had gone into the blazing buildings. People in the images came by to say, “That’s me, I was there, I survived”. A woman from Queens bought prints worth $2,900 for her church, a businessman from Texas bought hundreds to give as mementos at Christmas. Bill Clinton showed up with Kevin Spacey, Elton John passed by. There was something about the collective multiplicity of images, the sense of being surrounded by them, that made it all so potent.

Inspired by a snapshot Shulan had taken of laundry in Naples, they hung them overhead on wire. They went up anonymously or, as Shulan says, “No names, no frames.” The subtitle of the show was A Democracy of Photographs. “The pictures surround you, it’s inescapable,” says Richard Rutkowski, whose picture of a woman on Brooklyn Bridge became one of the most popular at Here is New York. “When you’re in that space, you can’t escape it. And you confront your feelings about it and you’re shoulder to shoulder with dozens of other people and they’re all going through the same thing.”

Inspired by a snapshot Shulan had taken of laundry in Naples, they hung them overhead on wire. They went up anonymously or, as Shulan says, “No names, no frames.” The subtitle of the show was A Democracy of Photographs. “The pictures surround you, it’s inescapable,” says Richard Rutkowski, whose picture of a woman on Brooklyn Bridge became one of the most popular at Here is New York. “When you’re in that space, you can’t escape it. And you confront your feelings about it and you’re shoulder to shoulder with dozens of other people and they’re all going through the same thing.”

The show opened on September 25; it was to close on October 15, but this was pushed back to Christmas. By December 24, more than 30,000 prints had been sold, the waiting time was eight weeks, the volunteers (I was one of them) worked around the clock, including Christmas Day when there was dinner in the gallery and photos hung on a tree.

Other cities clamoured for the show and Shulan and his friends found themselves with a true phenomenon. The book is already on its way to becoming a bestseller in the US.

“Photography was the perfect medium to express what happened on 9/11, since it is democratic by its very nature and infinitely reproducible,” Shulan says. “To New Yorkers, this wasn’t a news story: it was an unabsorbable nightmare. In order to come to grips with all of the imagery that was haunting us, it was essential, we thought, to reclaim it from the media and stare at it without flinching.” And, as he concludes in the book of Here is New York, “Seeing is not only believing. Seeing is seeing.”

· The Here is New York exhibition opens at the Guardian Newsroom, 60 Farringdon Road, London EC1, tomorrow and will run until October 5 (Mon-Fri 10am-5pm; Sat-Sun noon-5pm). Entrance free. A book, Here is New York, is published by Scalo/Thames & Hudson at £35.